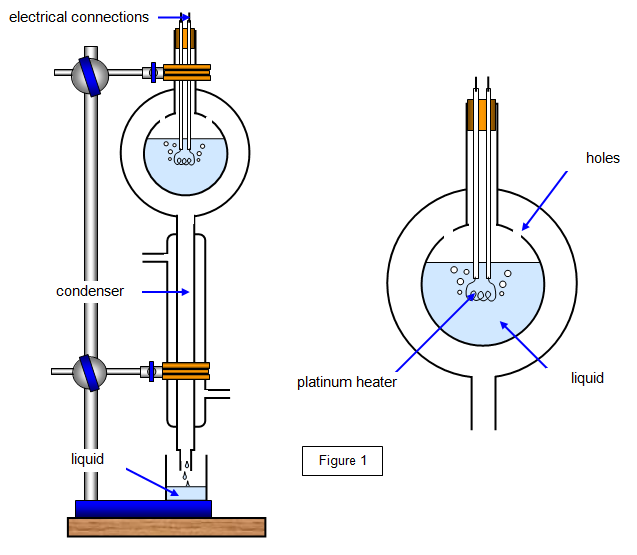

The specific latent heat of vaporization of a liquid may be measured by a modification of the method of Ramsey and Marshall (1896). The apparatus is shown in Figure 1.

The double-walled glass vessel is fitted to a condenser and mounted

vertically. The inner section contains the liquid in which is a heater made of platinum wire. When

the liquid boils the vapour passes through small holes into the outer vessel and then down into

the condenser. Here it condenses, runs down and is collected in the beaker. It is essential that

evaporation is rapid, for then the vapour in the outer vessel acts as a heat shield and eliminates

heat losses from the inner vessel.

When a steady state has been reached - that is,

when liquid drips into the beaker at a constant rate - a clean beaker is placed under the

condenser and the mass of liquid m condensing, and hence being evaporated, in a measured

time t can be found.

The specific latent heat of vaporisation L of the liquid can then be found

from the equation

where VI is

the power supplied to the coil. If a joule-meter is available the energy input E may be measured

directly; then

Energy input (E) = mL

The large specific latent heat of vaporization of water

explains why it is much more painful to be scalded by steam at 100 oC than by an equal

mass of liquid water at 100 oC. The steam first condenses before it cools to your body

temperature and in doing so releases roughly ten times as much heat energy as it does in the

cooling phase.

The simplest method for measuring this quantity is the method of mixtures. Ice is

dropped into water a few degrees above room temperature, and the resulting fall in temperature

is recorded after all the ice has melted. Since the water falls from a few degrees above the

temperature of the surroundings to a few degrees below the heat losses may be ignored - the

mixture is assumed to gain as much heat as it losses and a cooling correction need not be

applied.

(See also:

Latent heat of fusion experiment