PET scans have a variety of uses in medicine, particlarly in the study and treatment of cancer.

A PET scan shows whether the cancer is active or not.

It shows if it possible to remove the cancer by surgery.

PET scans are often used to diagnose a condition or how a condition is developing.

PET scans are often combined with computerised tomography (CT) scans or Magnetic resonance (MRI) scans to produce even more detailed images.

Before the scan takes place a small amount of radioactive material is injected into the body, this is carried round by the bloodstream, collecting in certain areas. This is called a tracer. This fluid usually takes about an hour to travel round the body, allowing cells to absorb it.

In a PET scan this tracer is usually an isotope of fluorine (fluorine 18) attached, or tagged, to glucose molecules. The result is that the fluorine is part of special glucose molecules, known as fludeoxyglucose, or FDG-18 which is a radioactive form of glucose (chemical formula C6H1118FO5) and this travels to areas where glucose is used cancer cells have a high glucose uptake which may be as many as 20 times that of ordinary cells.

A typical dose would be 14 mSv, about half that received per year from an airliner cruising at altitude.

Fluorine -18 is a positron emitter with a half-life of 108 minutes (1.80 hours) this means that the radioactivity in your body halves every 108 minutes. As an example, if you have the injection at 10.00 a.m. the radioactivity will have fallen to about 4.5% of its original value by 6.00 p.m, and by 10.00 the following morning this would have dropped to 0.01%.

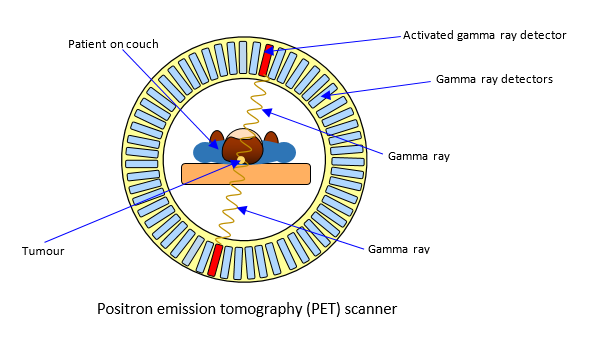

The positrons emitted collide with electrons and in each collision the particles are annihilated giving off two gamma rays. It is these gamma rays that are recorded by the detectors. The paths of the two gamma rays must be at 180o to each other to satisfy the conservation of momentum.