Kirchhoff's Rules

These two important rules apply to all electrical circuits and

are particularly helpful when dealing with branched circuits:

1. The algebraic sum of the currents at a junction is

zero. In other words there is no build up of charge at a junction

2. The sum of the

changes in potential round a closed circuit must be zero.

Rule 1 is about charge

conservation while rule 2 is about energy conservation.

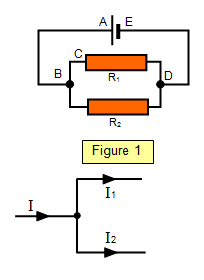

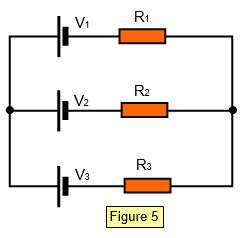

We can see how these rules work

by considering the circuit shown in Figure 1.

Rule 1At the point B there is a

junction

Current flowing from the cell (I) = Current in R

1 (I

1) + current in R

2

(I

2)

Rule 2

Round loop A,B,C,D,E: p.d across cell = - p.d across

R

1 This represents a gain of potential in the cell but a loss in R

1

Round loop B,C,D,B: p.d across R

1 = - pd across R

2 In this

equation there is a minus because we are moving 'against' the current in R

2

An

example of the use of Kirchhoff's laws

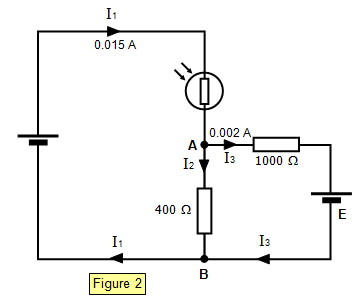

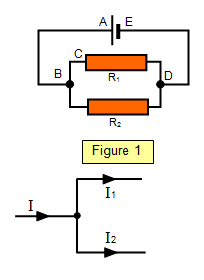

Applying Kirchhoff's first law to junction

A:

Current in the 400 Ω resistor = 0.015 – 0.002 =

0.013 A

Potential difference across 400 Ω

resistor = 0.013x400 = 5.2 V

This is the potential difference between A and B

via the 400 Ω resistor but it is also the potential

difference across the right hand branch of the circuit via the 1000 Ω resistor and the cell of e.m.f

E.

The potential difference across the 1000 Ω resistor is:

IR = I

3x1000 = 0.002x1000 = 2

V

Applying Kirchhoff's second law to the right hand branch and

considering an anticlockwise direction from the cell:

E.M.F of the cell

(E) = -0.002x1000 + 5.2 = -2 + 5.2 = 3.2 V

The minus sign is there

because the current in the 1000 Ω resistor is travelling in the opposite

direction to that in which the e.m.f of the cell is acting. Note that the potential difference between A and B is greater than the emf (E) of the cell.

Example problem

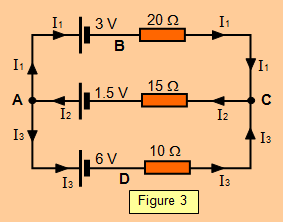

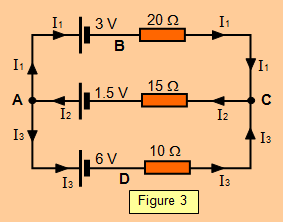

Consider the circuit shown in Figure 3.

Calculate the current shown in each resistor.

The directions of current have been chosen arbitrarily.

When we have finished the calculation it may be that

we have chosen them incorrectly.

If so we can simply reverse them on the diagram.

(a) Rule 1

Apply rule 1 to junction A

I

2 = I

1 + I

3 (1)

(b) Rule 2

(i) Choose the loop ABC

The sum of the e.m.f.s round this loop is the sum of the (IR) products in the loop.

1.5 – 3 = 20 I

1 + 15 I

2

Therefore: - 1.5 = 20 I

1 + 15 I

2 (2)

(ii) Now consider the loop ADC

The sum of the e.m.f.s round this loop is the sum of the (IR) products in the loop.

1.5 – 6 = 10 I

3 + 15 I

2

Therefore: - 4.5 = 10 I

3 + 15 I

2 (3)

Using equations 1 and 2: - 1.5 = 20 I

2 - 20

I

3 + 15 I

2 = 35 I

2 - 20 I

3 (4)

Now using equations 3 and 4: - 9 = 20 I3 + 30 I

2

Solving these gives: I

1 = 0.046 A, I

2 = - 0.162 A, I3 = - 0.208 A

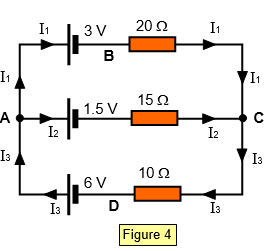

Notice that two of these currents calculated in

the example problem are negative. This means that we have chosen the wrong direction for these

currents in the original circuit.

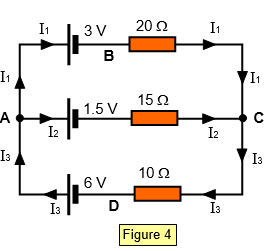

A circuit with the currents shown in their correct directions is

shown in Figure 4.

We can check the result by

considering the loop ABCD and using the original current directions.

6 – 3 = 3 = 20

I1 – 10 I3 = 20x0.046 - 10x(-0.208) = 0.92 + 2.08 = 3

This rule is rather

like going round a helter skelter. You start at the top and travel round, going down some slopes

and up others. Similar to the consideration of the potential differences met when 'travelling' round

an electrical circuit.

Problems

1. 20 identical light bulbs are connected in series across a 240V d.c supply.

(a) what is the p.d across each bulb

(b) what is the potential at the join of the second and third bulbs from the negative terminal?

2. If two cells, one of 4.5V and the other of 3V are connected in parallel what is the p.d across the junction between them?

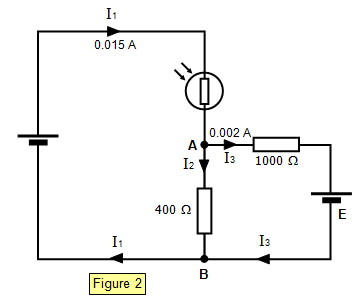

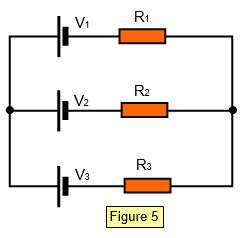

3. Calculate the currents in the three

resistors shown in Figure 5 for the values given below

(a) V

1 = 2 V V

2 = 4 V V

3 = 1.5 V

R

1 = 10 Ω R

2 = 15 ΩR

3 = 20 Ω

(b) V1 = 3 V V2 = 6 V V3 = 1.5 V

R1 = 4 Ω R2 = 8 Ω R3 = 12 Ω

(c) V1 = 6 V V2 = 3 V V3 = 1 V

R

1 = 16 Ω R

2 = 15 Ω R

3 = 8 Ω

A VERSION IN WORD IS AVAILABLE ON THE SCHOOLPHYSICS USB

(a) what is the p.d across each bulb

(a) what is the p.d across each bulb