A crystalline solid is one where

the internal structure is regular in nature, the atoms within it being set in well-defined

patterns. Some crystals are isotropic - that is, their physical

properties are the same in whichever direction they are measured, while others are anisotropic - their properties are different in different

directions.

Metals are generally polycrystalline materials, being composed of a large

number of small crystals or grains aligned in a variety of different directions. In metals the

atoms are held together by a cloud of free electrons that move between the

atoms.

Alloys are solid mixtures of two or more metals. An alloy will usually have

properties that are very different from those of the constituent metals. For example the

melting point of solder (50% lead and 50% tin) is 490 K while that of lead is 600 K and that

of tin is 505 K.

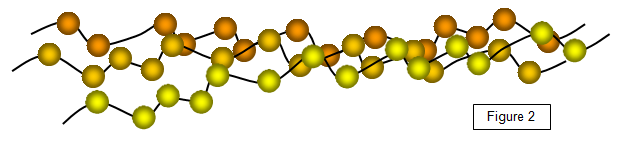

Figure 1 shows the structures of the four most common types of crystal

(for the moment we will assume that they are perfect and contain no impurities or

dislocations).

The four types are listed below together with one example of

each:

(i) face-centred cube - sodium chloride (FCC)

(ii) hexagonal close-

packed – zinc (HCP)

(iii) hody-centred cube – potassium (BCC)

(iv) tetrahedral –

silicon (T)

Note: The tetrahedral structure is shown in plan view and then as a

solid. The individual molecules have been shown different colours to make it easier to distinguish

between molecular plains.

The characteristics of each structure can be investigated

using the techniques of X-ray diffraction. In general, if the solid exhibits a regular structure as

shown by the first three crystalline states mentioned the X-ray diffraction pattern will show a

series of dots. If it is irregular, however, as in graphite in which the layers are free to slide

one over the other, a series of rings will result. (This can also be seen by the electron

diffraction through graphite).

The face-centred cube and the hexagonal close-

packed crystals are the most closely packed structures, and 60 per cent of all metals exist in

one or other of these forms.

An amorphous solid exhibits no regular internal structure; glass, plastic and soot are examples. In a way such a solid is like an instantaneous snapshot of a liquid, although one with an enormously great viscosity. An amorphous material has the density of a solid but the internal structure of a liquid. They are considered to be super-cooled liquids in which the molecules are arranged in a random manner similar to that of the liquid state. Amorphous solids are also unlike crystalline solids in that they do not have definite melting points.

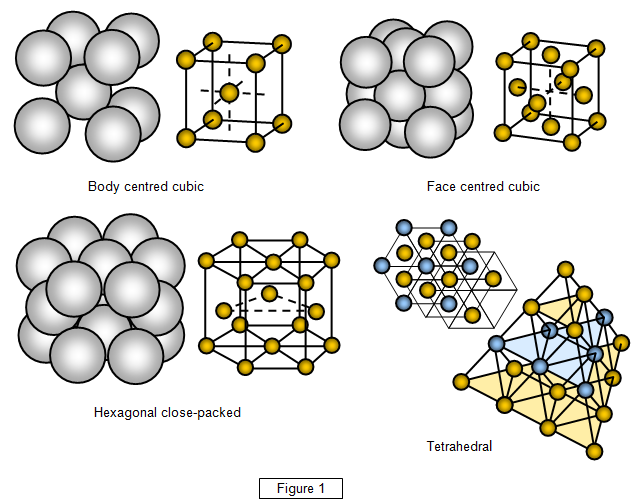

In these solids the molecules form long chains which

may contain anything between 1000 and 10 000 molecules. Many are natural organic

materials such as plant constituents but there are many synthetic polymers, one example

being polythene. The precise properties of the polymer depend on just how tightly these

chains of molecules are bound together. They may be tangled together in a haphazard way

or lie side by side.